We go back in time with the help of Associate Prof. Evgenia Kalinova from the Department of History at St. Kliment Ohridski Sofia University.

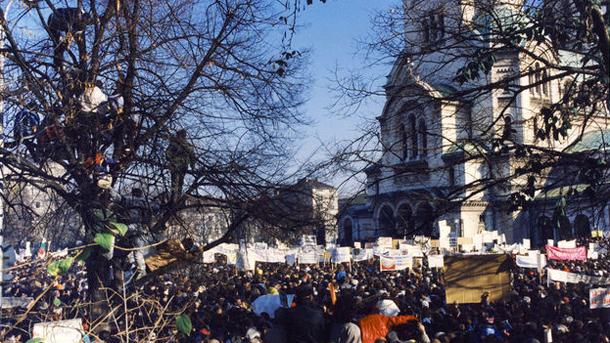

“Prior to 10 November there was hardly any viable opposition. Unfortunately it took the Bulgarian dissident movement longer time to emerge than in the rest of the Soviet Bloc. It doesn’t mean that just everybody accepted the communist regime. If you take intellectuals, many among them found ways to express their discontent, however not directly. The organized dissident movement began to emerge in the late 1980s, in 1988. The opposition played a role in the process, but it did not have any meaningful input into ousting Todor Zhivkov. The situation however changed dramatically in the days that followed 10 November. A few opposition structures were constituted, like for instance the Union of Democratic Forces. So, they indeed became a key factor in political development, but only in the aftermath of 10 November.”

To what extent was the process of change directed from high places?

“It was directed from high places. However, we have to be aware that public discontent was rising in the 1980s. A few factors were in place to aid the process, in the first place the economic crisis of 1980s”, Associate Prof. Kalinova says further. “Another factor had to do with the cataclysms caused by the forceful expulsion of the Bulgarian Turks to Turkey in 1989. So, discontent was strong, but hardly strong enough to result in ousting Todor Zhivkov. He was ousted by his closest associates, who were aware of the power of public discontent brewing around. As usual, changes in Bulgaria would be dependent on changes elsewhere, in this case in the former Soviet Union. The people surrounding Zhivkov, but also related to the Soviet Union, decided to oust him, and changes began to roll more quickly. Even they however, did not think of replacing the whole system. They aimed to topple Zhivkov, take his place and launch changes that would guarantee the positions of the Communist Party. The reform-minded communists wanted to act with a new image of party reformers. However the developments across Eastern Europe that followed spoiled the plans of the communist party that had in the meantime changed its name to socialist.”

You have written monographs on Bulgaria’s recent past. Has transition completed?

“I have to make two points here. One is the emotion, the public sentiments. Obviously people believe that transition should end with an outcome that will make them feel better and live better. In this sense, the public mind tends to believe that transition is not complete. If however, we take a scholarly point of view, then transition is complete, because the one-party, totalitarian system has been dismantled. In economic terms however, the issue is much more complex, notably the transformation of state into private property plus the implementation of market mechanisms. This has gradually taken place, and Bulgaria was acknowledged as a country with a market economy. In an international perspective, Bulgaria’s membership of the Warsaw Pact and the Soviet Bloc has been replaced with its accession to Nato and the European Union. To recap: Bulgaria has completed its transition. The fact that the outcomes are disappointing for the people is another question.”

“People have become poorer – the greater part of them, and few have become richer”, Krassen Vassilev, 34, says. “Well, there are both good and bad things in the story, but the general feeling is of some sort of quasi-democracy, of an inertia from all that has been happening globally, rather than an achievement of Bulgaria’s domestic democracy. Society has been divided into castes, and each of them has taken its own cage.”

“The good things are few”, Elka Stavreva, 31, contends. “We can’t possibly buy many things from the stores, but at least they are full of choices. There is a great diversity, in material terms, that is. There are many cinema halls, we can watch many movies, not all of them high-quality, of course, but at least there is choice, and we didn’t’ have that before. Now we can be openly critical of the government as well.”

“Many things have changed during transition”, says Danko Hristov, 52. “The lives of its contemporaries changed profoundly. We moved from a carefree and secure existence to the present-day situation when people are distressed with how to cope tomorrow, and the day after tomorrow. The way in which transition was implemented was wrong, so now we have to pay a very cruel price. Well, thank God, Bulgarians are quite tough and are proven survivors after various experiments. This shows in people’s behavior. They seem reconciled with what has been happening to them. They hope that things will get better some day. However, this depends on our way of accepting things, on the efforts we have to make, so that a real civil society could emerge.”

“In the past life proceeded within quite clear limits, and we had got accustomed to it”, Tinka Bakalova, 79, recalls. “Now it all looks like a big chaos. Everybody is free, but cannot possibly rely on either the state or society. Incomes are lower, and the cost of living is up. People are less responsible. I do not respect the government. I think it has nothing to do with our lives. They come and go. There is an ongoing political struggle and we are simply spectators, left to cope on their own.”

On Bulgarian transition we talked with analyst Antoni Galabov.

What is the stocktaking for the last 20 years of democratic changes?

“In the first place, we have to admit that Bulgaria has wasted some time in the process of reform. There were influential and well-organized groups that acted against reform. From 5 to 7 years of our lives were wasted in reforms that either went wrong or were compromised. On the other hand, though with some delay Bulgaria was put on the map of the development of the European countries. From now on we have to try to make up for the lost time.”

What did change produce: more disenchantment or more approval?

“The Bulgarian society was badly hurt by social inequality perceived as painfully unfair. The Bulgarian public mind is dominated by a feeling of great injustice. Even the social groups that have benefited from the changes still view them as unfair, as having occurred under pressure from abroad and as a result of illegitimate corporate interests. That is why at the end of this 20-year period what we formally have is a kind of a façade democracy. We do not have the democratic mechanisms of government, of civil involvement and of reciprocal control of powers that in the end guarantees the freedom of anyone of us.”

Who were and winners and the losers?

“It is hard to judge. In the short term, the former elites are the winners. The transformation and even mutation of the totalitarian system was a process controlled by the former elites of the economic and party nomenclature of the Bulgarian Communist Party. They and their children ruled the country for certain periods of time. They have gained the confidence of staying in power for a long time. Their families and family relations went through the whole of that period. In a strategic perspective however this rather false and even meaningless group of people have to realize that their mimicry is not what present-day life can tolerate. The more we drift away from this period, the more it looks ridiculous, barbarian and anti-human. So, from a strategic point of you, all of them are losers.”

Associate Prof. Tatiana Burudjieva, political analyst, brings her insights. What is specific about the Bulgarian transformation?

“There are two specific traits. In the first place, the market economy mechanisms started to get introduced to Bulgaria too late – in 1992, meaning that liberal democracy functions with difficulties here. Secondly, Bulgaria as a society, preoccupied with the ambition to join Nato and EU, failed to work on the three types of efficiency of society that were focal for the rest of the former communist countries. These include the economic, social and political efficiency that can guarantee the emergence of a true democracy in terms of quality of life. In Bulgaria this has failed to take place."Has civil society matured over those 20 years?

“A civil society requires citizens. Do we have such citizens? I don’t think so. The citizens are only keen to see the shortcomings of the political class. I think that there are certain micro-civil societies in which everybody is trying to survive, and gain some self-confidence.”

Are there any achievements for the last 20 years?

“Yes, of course. The problem is that those achievements are within the limits of façade democracy. There are democratic institutions; there is a party system and a market economy, as well as a social security system. However, all this looks like a piecemeal job. These structures do not involve the energy of all citizens. As a result even real successes are perceived as either failures or exceptions from the rule. Talking about society we have to bear in mind that self-esteem is key. Sometimes people in less successful societies live better, because they can sense where they go, they know what they do, and they are convinced that they work to the benefit of their children. In Bulgaria this prospect is lost, and this powerfully deforms both the evaluation and the ideas of the present-day reality.”

Zhivko Todorov was 8 when transition to democracy started in Bulgaria. Today he is an MP for the center-right party Gerb. He has graduated in European Studies. Are young people interested in Bulgaria’s past?

“For sure, a greater part of them is interested in the past. It is only logical for young people to ask questions about the past and where we are heading. So we go back in time, we want to see what life was like prior to 1989. We analyze the communist regime when there was neither democracy, nor market economy. There were no freedoms that are provided by our EU membership. Life was very much closed within one country and one party. As a result we believe that today the situation is better, because we can benefit from the freedom of travel, of work and study, and from the freedom of speech too. Now the opportunities are much greater for anyone of us.”

What are the problems of young people like you?

“Despite 20 years of transition, young people still have problems that have to do with their education in the first place, secondly, with their career growth, and thirdly with their security. A young individual needs high-quality education to be able to grow professionally and find a good well-paid job. In Bulgaria we are lagging behind with the standards providing for excellent education. Security is a key challenge too. The insecurity in the street, widespread aggression in schools and even in discos – all this frustrates young people, and a lot has to be done in this respect.

What opportunities for the young does EU membership create?

“The EU gives great opportunities that our parents never enjoyed”, Zhivko Todorov says further. “There is a diversity of youth programmes for education and exchange. We are free to communicate with our coevals abroad. This means that we can broaden our views. We are able to work and study in other countries. In fact the greater opportunities created by EU are mostly for young people.”

English version: Daniela Konstantinova

Every child dreams of having all the time in the world in which to play and enjoy piles of sweet delights. One of the most favorite, of course, is His Majesty the Chocolate. The first records of its appearance can be found as early as 2,000 years before..

A little over 1,450 Leva is the sum needed per month by an individual living in a one-person household, and a total of 2,616 Leva for the monthly upkeep of a three-member household - as is the most widespread model in Bulgaria at the moment (two..

The traditional "Easter Workshop" will be held from April 23 to 26 in the Ethnographic Exposition of the Regional History Museum - Pazardzhik. Specialists from the ethnographic department of the museum will demonstrate traditional techniques and..

A little over 1,450 Leva is the sum needed per month by an individual living in a one-person household, and a total of 2,616 Leva for the monthly..

Every child dreams of having all the time in the world in which to play and enjoy piles of sweet delights. One of the most favorite, of course, is His..

+359 2 9336 661