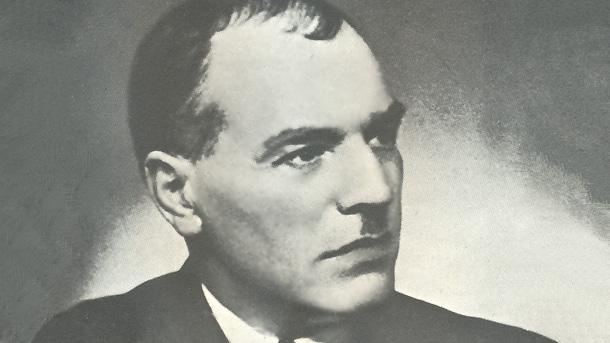

-14:0-58:0-42 до годишните награди на БНР "Сирак Скитник"

Unlike the early start in the career of the other great Bulgarian story-teller of his generation Elin Pelin, Yovkov’s official debut with a short story was at the mature age of 30. His military experience had already produced a writer excelling in keen observation and boasting a flawless memory. His native village Zheravna, huddled high in a wooded mountain, inspired him for the fascinating cycle of stories Legends of Stara Planina (alternatively known as Balkan Legends, 1927). The flat farming fields of Dobrudja enriched his writing perspective for his later mastery cycles of stories, The Inn at Antimovo (1928) and If They Could Speak (1936). Zheravna and Dobrudja provided the two spatial and spiritual mainstays for Yovkov. Critic Ivan Sarandev once wrote that “the field and the mountain find a point of contact in Yovkov’s work”.

* * * Yordan Yovkov’s cardinal contribution into the national literature derives from his profound humanism, subtle portrayal of the birth and demise of human illusions and an unbeatable yearning for beauty. Further on, the moral code of the writer is tuned to specific laws with basic norms identified as stamina, beauty, youth and valor. He emerged as the foremost romantic in Bulgarian literature for his concept about man and the world. In the meantime, his narrative is strongly branded with psychological realism. The guiding light in his creative quests had been provided by the great Russian story-tellers Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Chekhov. Yovkov was also the writer, who took a by-lane, thus shyly and elegantly breaking away from the national narrative tradition. In his monograph about him critic Simeon Soultanov wrote the following: “Yovkov made obvious a clash previously unexplored – of the ego with the alter-ego.” And here is the observation of literary critic Svetlozar Igov: “The new anthropocentric era in literature did not only replace the old community, group values with the values of the individual, but transformed the ethnocentric spatial focus (The Balkan Range) into new ones, notably, The Plain, The Inn and the Farm”. And indeed, as early as the cycle Balkan Legends, Yovkov’s protagonists were already descending from the legendary and heroic mountain to the new destinations of the self.

Yordan Yovkov’s cardinal contribution into the national literature derives from his profound humanism, subtle portrayal of the birth and demise of human illusions and an unbeatable yearning for beauty. Further on, the moral code of the writer is tuned to specific laws with basic norms identified as stamina, beauty, youth and valor. He emerged as the foremost romantic in Bulgarian literature for his concept about man and the world. In the meantime, his narrative is strongly branded with psychological realism. The guiding light in his creative quests had been provided by the great Russian story-tellers Tolstoy, Dostoevsky and Chekhov. Yovkov was also the writer, who took a by-lane, thus shyly and elegantly breaking away from the national narrative tradition. In his monograph about him critic Simeon Soultanov wrote the following: “Yovkov made obvious a clash previously unexplored – of the ego with the alter-ego.” And here is the observation of literary critic Svetlozar Igov: “The new anthropocentric era in literature did not only replace the old community, group values with the values of the individual, but transformed the ethnocentric spatial focus (The Balkan Range) into new ones, notably, The Plain, The Inn and the Farm”. And indeed, as early as the cycle Balkan Legends, Yovkov’s protagonists were already descending from the legendary and heroic mountain to the new destinations of the self.

Taking a detour from the ethnocentric values into anthropocentric ones, Yovkov won a victory over the limiting regional quality of Bulgarian literature that has troubled many writers before and after him. He is truly universal in his remarkable cult for beauty which he is eager to discover everywhere: in feminine beauty but also in the grace of creative work and of a bunch of white roses. His detailed and picturesque narrative style coupled with great psychological depth explains why his works are markedly cinematographic and are the basis of a few very successful feature films. Yovkov himself was a gifted playwright and this shows in his classical plays Albena and Boryana.

* * *

Mastering his short stories Yordan Yovkov worked to bind them in cycles. In Legends of Stara Planina he revisited the past of his native region: not as a chronology of history though but as crystallized human experience. The protagonists are exceptional, portrayed in due scale. They are larger than life set against the mountain scenery. The cycle harmoniously marries the themes of youth and valor, beauty and love to highlight their cathartic quality.

While in Legends of Stara Planina Yovkov is preoccupied with singularity in life, the volume The Inn at Antimovo reveals its repeatability. The Inn is like a magnet for a bunch of protagonists who are strikingly unusual – both rich and generous. It is not a place to live, rather it is the place to enjoy and take a break from routine.

The short story turned play Albena is telltale of Yordan Yovkov’s moral code. The key to it is the phrase: “The woman was guilty but she was beautiful". Albena with her lover Nyagoul has killed her husband Koutsar. However her beauty mesmerizes the originally angry village crowd and she is morally redeemed. The writer justifies her because of her almost magic beauty.

* * *

Albena was the same Albena – just that she wasn’t laughing, her eyes weren’t flirting as before but were cast down under her thin brows. She was wearing a blue dress and a fox lined jacket. She was clasping her hands meekly to the front as though she was going to church. But when she found herself between the two walls of people and she lifted her eyes, that look which every man knew, had become even more beautiful because it was drawn in grief and those thin eyebrows and that white face – it was as if a calming binding spell had wafted from her. The woman was guilty but she was beautiful. The women who’d planned to heap abuse on her head fell silent and even Daddy Vlasio’s stick didn’t move.

And in that silence, in those few moments a miracle happened, even the hardest hearts were moved, sympathy and goodwill shone in the eyes of every man and woman.

“Well, well Albena, lass!” a female voice choked with tears. “What did you do Albena!”

Translation by Christopher Buxton

* * *