The date of January 27 has once again arrived - the day on which the few survivors of the Auschwitz concentration camp were released in 1945. Decades later, the United Nations Organization turned this date into an International Holocaust Remembrance Day, encouraging not only respect for the victims but also the accumulation of knowledge so that this genocide would never happen again. In memory of the victims, a museum of the Holocaust and Jewish Resistance Heritage "Beit Lohamei HaGhetaot" (The Ghetto Fighters’ House) was established in 1949 in the Jewish state of Israel, which was restored after the Second World War.

The museum, named after the Jewish poet Itzhak Katzenelson who died in Auschwitz, is located in Galilee, in the kibbutz of Lohamei HaGhetaot, established by former activists of the Jewish resistance against the Nazis in Poland and Lithuania.

Anat Livne, a long-time researcher and director of Beit Lohamei HaGheataot, grew up in the Bulgarian kibbutz Beit HaShita, near the Sea of Galilee. In the past, her grandfather was the principal of the Tarbut Jewish School in the Bulgarian capital Sofia, and her grandmother taught there until 1939. When the family arrived in Israel, they were among the founders of the Lohamei HaGheataot kibbutz. It housed children and young people from concentration camps and ghettos throughout Europe.

Unlike her mother who inherited the teaching profession from her parents in Bulgaria, Anat Livne decided to dedicate herself to history. She wanted to find an answer to a paradox - why Polish Jews, like her father, could not escape the death camps and how the Bulgarian Jews managed to do so.

Every year, around January 27th, World War II survivors are invited to talk about the suffering and humiliation experienced in the concentration camps. Anat Livne, however, opposes the abuse of the feelings of people who still bear the "guilt" that they survived unlike their loved ones. Of course, this does not mean that the memory of those who died and what happened in Europe must sink into oblivion - the memory of them can be passed on through conferences, works of art, and not in show ceremonies. Due to her "heretical" statements, Anat Livne's contract at the museum was not extended.

However, Anat Livne keeps the memory of the most interesting archival materials in the museum which were stored in the Warsaw ghetto.

"Some of these priceless exhibits were handed over by members of the illegal youth group Dror, who would sneak out of the Warsaw ghetto and return with food, news from the battle front, and sometimes weapons," Anat Livne explains. "These young people knew every hole in the fence, the road through the sewers, the unknown underground passages, and that's why they managed to save themselves."

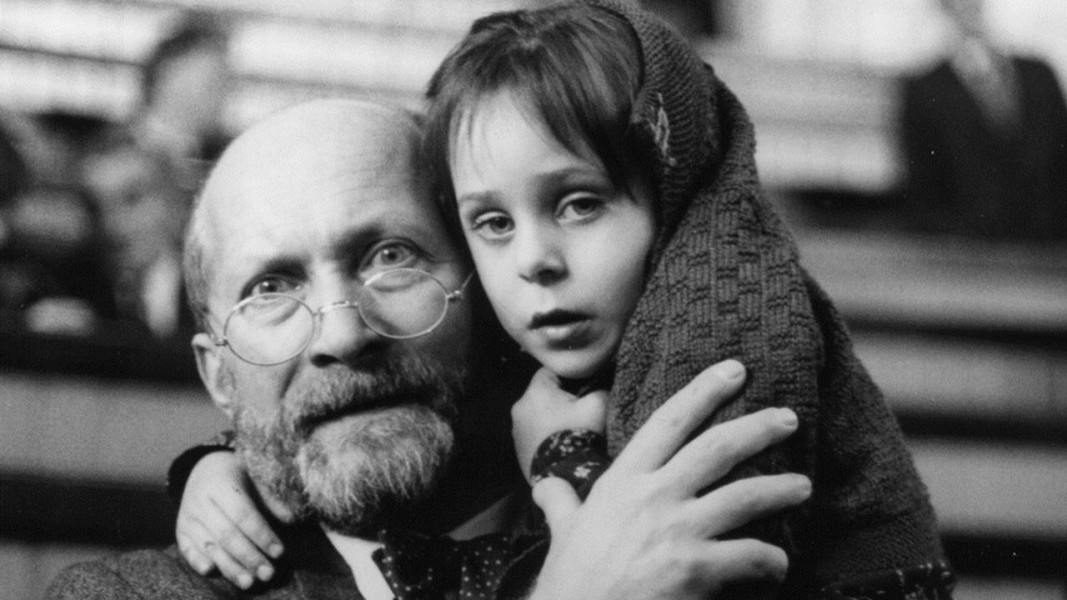

One of the precious exhibits in the museum is the briefcase with documents and personal belongings of the genius pedagogue Janusz Korczak, who voluntarily accompanied the children from his Jewish orphanage in the Warsaw ghetto to Treblinka and entered the gas chambers with them.

"In his works, he regards each child from the moment of birth as a person with his or her own rights and opinions from an early age,” Anat Livne continues her story. “At that time, the kids did not read his works or his stories, but they were lucky to talk to him and be inspired by his incredible views. Janusz Korczak believed that all people are brothers - it doesn't matter what ethnicity the child is, what matters is how the child lives in order to be happy."

The prominent educator ran two orphanages - one for Jewish children and another one for Polish orphans. He also hosted his own show on the Polish radio, in which children also participated. People knew him as a great Polish pedagogue, but not everyone knew his birth name was Henryk Goldszmit.

"In the ghetto, Janusz Korczak did not differentiate between local children and those in the orphanage and often distributed the scarce food to orphaned children outside the home," said Anat Livne. “The German guards were so awestruck by him that an officer offered to take him out of the ghetto when the deportations to the death camps began. But he chose to stay with the children whom he encouraged until the very last moment."

Shortly before he was taken away, Janusz Korczak managed to hand over to a member of Dror a briefcase with an unfinished scientific work on pedagogy, documents from the orphanage, personal belongings and some money. The young men hid it in a hiding place and after the war they searched for it and took him to Israel. The briefcase is the last vestige left by the great educator and pedagogue. The museum managed to restore this remaining heritage and today it is the most valuable possession in its exhibition fund.

Written by Fenya Dekalo and Iskra Dekalo

Edited by Darina Grigorova

English version Rositsa Petkova

Photos: archive, gfh.org.il, and private library