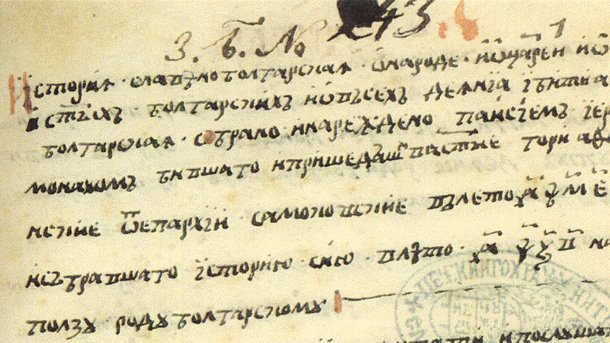

Back in 1762 in his cell on Mount Athos, a Bulgarian monk, Paisius, completed a thin book that was to have an unusual destiny. Close to 370 years after Bulgaria was conquered by the Ottoman Empire the glorious past of the Bulgarian kingdom was almost completely forgotten. Bulgaria’s remarkable kings, clerics and warriors were no longer present in the nation’s memory. In a foreword to his book Slav-Bulgarian History Paisius of Hilendar turned to our compatriots in the following way: „Read and know so that other tribes and peoples will not mock and reproach you. I have come to love very deeply the Bulgarian people and fatherland and I worked hard to collect material from various books and history books until I gathered and compiled the history of the Bulgarian people in this little book for your use and praise. I wrote it for you who love your kin and the Bulgarian fatherland. Copy this little history and let others copy it for you those who know how to write, and keep it from disappearing!”

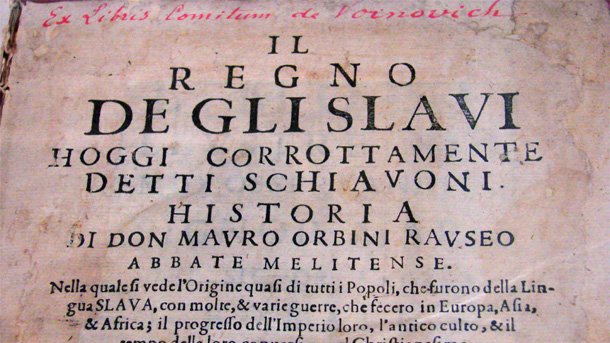

Paisius’s work was charged with colossal patriotic energy. However it was not an isolated phenomenon. Catholic priest Hristofor Zhefarovic in 17 c., artist and writer, Franciscan monk Blasius Kleiner in 18 c. and others released texts exploring Bulgarian history. They prepared the ground for Slav-Bulgarian History that emerged in a fateful moment for Bulgarians.

„The mid-18 c. was an interesting time. On the one hand, this was a time when Hellenism took a major offensive”, explains Alexander Moshev from the National Museum of Literature. “Relying on its clerical power the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul intensified the process of hellenization of the Bulgarian society. And the celebrated appeal of Paisius, ‘Oh, you unwise man! Why are you ashamed of calling yourself Bulgarian and why don’t you read and speak your language’ was actually addressed to that part of Bulgarians who were willing to accept Hellenism. Besides, in 1767, a few years after Slav-Bulgarian History was written, the Bishopric in Ohrid, today in the Republic of Macedonia was annihilated. It had been the last stronghold of the Bulgarian national spirit. On the other hand, the impulses of the Enlightenment in West Europe began to spread to the Balkans. The ideas of Voltaire and Rousseau had been accepted in this part of Europe creating an interesting cultural and political context in which people like Paisius were born and worked.”

The small book was destined to play an exceptional role in the Bulgarian National Revival. Touring the Bulgarian lands Paisius always had the book with him for it to be copied and read by Bulgarians.

„Literary evidence mentions seventy copies. Physically, only 45 of them have survived to the present day, and the copyists of the great book include renowned figures such as Petko Slaveykov and Hristaki Pavlovic,” Alexander Moshev goes on to say. “In fact the first copy from 1765 was made by Sophronius of Vratsa and the last one was made in 1882 by priest Kostadin Chuchulain from the town of Bansko. You can imagine what huge chronological scope the copies of the History had! Its life through the copies was very important as they also reflected the personal attitudes of copyists, as well as of the people who would be listening to texts from them read aloud. Given the then-level of literacy people gathered together to have passages from the History read aloud to them. In this way the message for the national awareness of Bulgarians reached a very wide audience.”

As to Paisius, he was somewhat overshadowed by his Slav-Bulgarian History. There is little evidence about his life and it mostly comes from the book, from the archives of the Hilendar Monastery on Mount Athos and from a few letters. In this way his personality has remained a secret. In 19 and 20 c. various hypotheses emerged about his town of birth: the town of Bansko, the village of Dospey and the village of Kralev Dol all in Western Bulgaria. As scholar Petar Dinekov remarked in the preface to the 1972 edition of the Slav-Bulgarian History, the most trustworthy hypotheses ended up in Bansko. It is known that Paisius was born in 1722 and it is assumed he died in 1773 in the village of Ambelino, today part of Assenovgrad, Southern Bulgaria. From then on the legend began…

Paisius of Hilendar was canonized as saint by the Bulgarian Orthodox Church in 1962. An exhibition mounted at the National Museum of Literature in Sofia is dedicated to the 250th anniversary of Slav-Bulgarian History and to his 290th birth anniversary. In May it was shown at the Sofia City Library. It features the chronicle writing traditions of Bulgarians from the early Middle Ages to the Paisius era, as well as the sources that he used to write his work. There is material about the discussions on Paisius biography as well as the way Slav-Bulgarian History was accepted over time. Apart from the handwritten copies it has had many printed editions. Today, in an act of veneration to his great work, pupils from various parts of Bulgaria still copy his eternal Slav-Bulgarian History.

Translated by Daniela Konstantinova