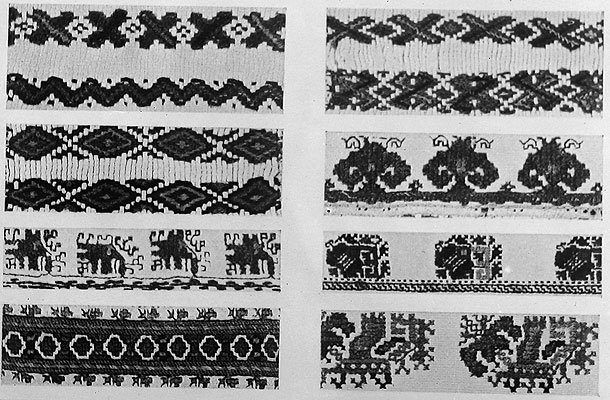

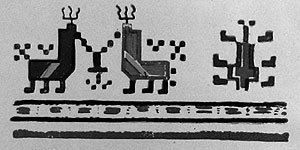

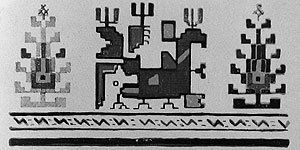

Bulgaria’s greatest scholar in Bulgarian social psychology Ivan Hadjiiski once said that Bulgarians were not very talkative. As compensation, however they opted for the language of visuals and depiction that tends to be more impressive and more easily – and emotionally, digested. In times of old when Bulgarians communicated on markets, fairs and during holidays, the male and female costumes would clearly suggest their family and general social status. Teenage boys and girls would wear the same costumes without any gender distinction. Various elements in female clothing would indicate whether the girl or woman was still in puberty, already engaged, a young bride or a widow. The female waist-belt had tassels. The maiden would attach the tassels on the left, while the married woman – on the right. If a teenage girl had a sweetheart, she would change the position of the posy that she wore – from the left to the right. So, if anybody happened to fancy her, he would become aware he had nothing to hope for. The Bulgarian folk costumes are excessively rich in ornaments and in color. The folk costume thus mirrors the crossroad East-West location of the Bulgarian lands. This place has hosted the encounter of various peoples and cultures – Thracians, Proto-Bulgarians and Slavs. Cumans, Avars, Tatars passed by and even settled here. This incredible ethnic wealth has found adequate expression in the wealth of the Bulgarian folk costume, ethnographer Prof. Ganka Mikhailova explains. One quite remarkable element of the folk costume is the embroidery:

© Photo: Miglena Ivanova

“Three days before the wedding, the whole trousseau, including the gifts that she had prepared for the in-laws was arranged in the walls, and bigger pieces were displayed on the fence”, Prof. Ganka Mikhailova goes on to say. “The whole village community came to have a glimpse at the trousseau, especially the master-women who turned clothes to look at their reverse side. And clothes were made in a way so as to make possible for the reverse side to be worn as the right side – there should be not a single knot or a sewing mistake. However, there was always an incomplete element – against evil eyes, because too good was no good news. And besides, perfection is impossible. And in the traditional philosophy the imperfection should be on the product rather than become part of the process of reproduction itself.

And given that everything in making clothes was strictly regulated, a woman who chose to marry outside her native village, was virtually mourned. As social psychologist Ivan Hadjiiski wrote, „life outside the village is life abroad”. The bride left with the trousseau, but it failed to fit in the new place as it had its original traditional clothes in terms of fabrics and embroidery patterns. She had no time to make new clothes busy to give birth once every two years and to work in the field. So such a woman remained outside the social context and pretty isolated in her new village.

The folk costume is a universe with its specific language. However due to that we do not know it well, we, present-day Bulgarians, are kind of lost in translation, ethnographer Prof. Ganka Mikhailova says in conclusion.

Translated by Daniela Konstantinova

Photos: Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

In the Bulgarian folk tradition, the feasts of Lazarus Saturday and Palm Sunday are related holidays. From Lazarus Saturday (Lazarovden in Bulgaria), girls prepare for the ritual kumichene, which is performed on the morning of Palm Sunday. A very old..

In April and May the visitors of the Strelcha Historical Museum will have the opportunity to get acquainted with the traditions connected with the Easter holiday cycle through the exhibition A Fine Easter, a Finer St. George’s Day . Easter..

Lazarus Saturday is widely known in Bulgaria as Lazarovden , celebrated by Orthodox Bulgarians on the day before Palm Sunday. The main rite is the lazaruvane - a traditional custom centred on themes of love and marriage. Girls over the age of 16,..

+359 2 9336 661