"How many people in our history can be called apostles? Today Bulgaria is a conflict-torn country where people are divided on every conceivable issue. Now, more than ever, we need unity, and there is no better unity than that around the memory of the Apostle," Minister of Culture Naiden Todorov said at the presentation of the National Programme to commemorate the 150th anniversary of the death of Vasil Levski. Yet the life of the Apostle of Freedom is still full of unknowns. Although every Bulgarian is familiar with the facts of his 36-year life from an early age, there are still details that cause controversy in the historical arena.

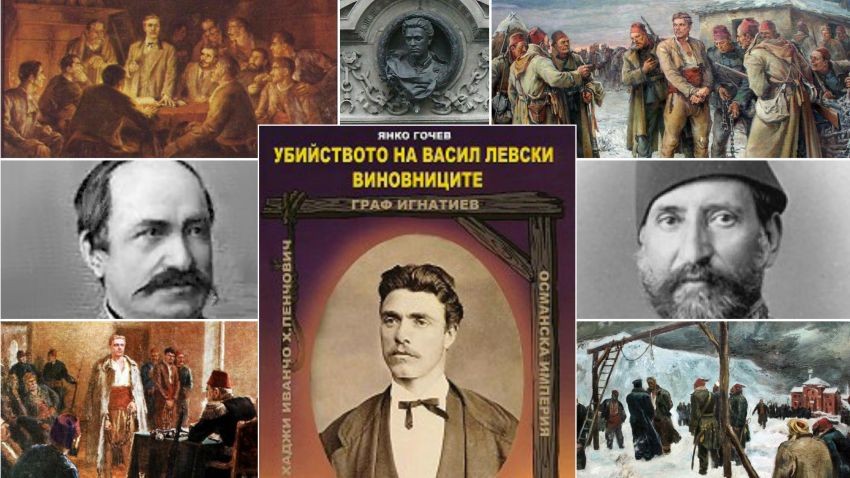

One of the controversial questions among historians is whether or not there was a trial against the Deacon before he was sentenced to death by hanging. In his book "The Murder of Vasil Levski-The Culprits", historian Yanko Gochev argues that there was no trial because the Special Investigation Commission in Sofia was not a court. The study helps to unravel other facts and contradictory statements related to Levski's personality, his influence and deeds for the cause of liberating Bulgaria from Ottoman rule.

"There was no trial because the members of the extraordinary government commission that met in Sofia in December 1872 and January 1873 were not lawyers, with the exception of Ivancho Hadjipenchovich. The body before which the Apostle was tried was also not a court of law, since there was no criminal procedure law under which the actions of the Revolutionary Committee's activists could be judged," the historian is adamant. - The commission appointed by the Ottoman government, with General Ali Said Pasha, a Georgian, as its chairman, carried out only an inquiry, which can only be provisionally called an investigation.

Rather, we are talking about an administrative proceeding that moves under the substantive - for there is no procedural - Ottoman criminal law. We are talking about the Imperial Penal Law of 1858, under which the commission examined the acts of the Revolutionary Committee activists, and then came up with 15 protocols, of which only 6 have reached us in Turkish transcripts, containing individual or group punishments."

The lack of an actual trial can be explained by the fact that there was no fully functioning legal system in the Ottoman Empire based on the European model. The Ottoman legal system underwent reform after the Crimean War (1853-1856), but this was a slow and difficult process, and criminal procedure as we know it today, in the 1870s, was out of the question.

"That is why I think that the thesis that there was a trial against Levski, which many historians defend, is not quite correct," explains Gochev.

In his legal-historical research, the author refers to numerous available historical sources, including documents from the archives of the National Library, the Central State Historical Archive, as well as all documents from foreign state archives published in Bulgarian and Russian.

It also disproves another speculation: that the Bulgarian people made no attempt to save Vasil Levski on the way to his death. The truth is that there were 8 such attempts, he says.

"Perhaps most well-known is the attempt of Atanas Uzunov, who formed a detachment which, if the Apostle was travelling to Constantinople, would attack the convoy in which he was moving and he would be liberated - says the historian - It is a lie that Vasil Levski was accompanied by only two guards, and the Bulgarians were inactive and did nothing for his liberation."

Yanko Gochev says that another attempt was made to rescue the Apostle "towards the end of 1872 and the beginning of 1873. Then envoys from the Revolutionary Committee of Turnov arrived in Serbia. The aim was to use the connections of revolutionaries Panayot Hitov and Lyuben Karavelov there, who, with the help of the Serbian government, would arrange his release". This did not happen, as Serbia had its own plans, which did not provide for the liberation of the Bulgarian people, nor for the unification of the Bulgarians within Bulgarian ethnic borders. Russia's top diplomatic representative in Constantinople, Nikolai Ignatiev, had the opportunity to save Levski himself because of his influence as doyen of the diplomatic corps.

Ignatiev, however, issued another order immediately after the Arabakonak* robbery. Preserved as a document, it provided for the rescue of only those revolutionaries who were undercover Russian agents, but not of Levski.

Until now, there are still white spots in Bulgarian historiography related to Levski's conflicts with Russian imperial policy and attempts to recruit him. Information about this conflict and his categorical refusal to cooperate exists and simply needs to be examined, historian Yanko Gochev is adamant.

*The Arabakonak robbery of an Ottoman postal ox-cart transporting the tax revenues from the Orhanie Teteven regions and was carried out on 22 September 1872 in the Arabakonak Pass. It was organized by revolutionary committees of the Internal Revolutionary Organization– ed.

English version: Elizabeth Radkova

THIS PROJECT IS REALIZED WITH THE FINANCIAL SUPPORT OF THE BULGARIAN MINISTRY OF CULTURE WITHIN THE FRAMEWORK OF THE NATIONAL PROGRAMME FOR THE COMMEMORATION OF THE 150TH ANNIVERSARY OF THE DEATH OF VASIL LEVSKI.

June 11, 2007 - US President George W. Bush Jr. visits Sofia. According to protocol, the press conference he held for the media took place among the exhibits of the National Archaeological Museum. The official lunch for the guest was later held at the..

On November 10, 1989, a plenum of the Central Committee of the Bulgarian Communist Party ousted its General Secretary and Chairman of the State Council, Todor Zhivkov. This marked the symbolic beginning of the transition from a one-party system to..

Archaeologists have explored a necropolis in the Kavatsi area near Sozopol. The perimeter in which it is located is part of the history of Apollonia Pontica and is dated to the 4th century BC. "This is a site with interesting burials in which a nuance..

Today, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church commemorates St. Naum of Ohrid. Naum was a medieval Bulgarian scholar and writer. He was born around 830 and..

The first modern Christmas was celebrated in Bulgaria in 1879. It followed a European model with a Christmas tree, ice skating and gifts. At that..

+359 2 9336 661