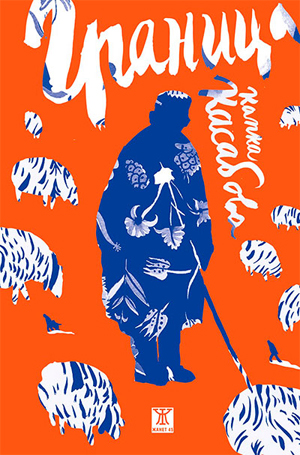

Borders – those of territories and ones that we draw within our own mind, alongside the challenge to walk across ban, fear and prejudice. Sometimes the price is our own life, but longing for freedom wins after all.

A Bulgarian novel has thrilled the reading community in Scotland. The Border stories of Kapka Kassabova sound like a warning in a world of Brexit and endangered by new separation. ”If ever there was a book for our times, it is Border, which delves into the stories of when the lines that separate countries on the map harden once more after their Cold War thaw. It is at once timely and timeless, with Kassabova the poet and travel writer blending skills to spin something truly magical and sadly, entirely necessary.” That is the motivation of the Saltire Literary Awards to announce Border: A Journey to the Edge of Europe as the Scottish Book of the Year.

In 2013-2016 the author journeyed along the border of Bulgaria with Turkey and Greece, with the idea of collecting previously unrecorded local stories. While wandering through the vast wilderness of the southern Rhodope and the Strandja ranges, she realised that people’s experiences on each side of the border had a mirror image on the other side. Collective and family traumas – the displacements after the Balkan Wars, The Great War, the Cold War, and forced migrations including that of the Bulgarian Turks in 1989 – are still in living memory. And all along this border, there is the awareness of the hundreds of unnamed graves of fugitives from Eastern Europe. Trying to cross into ‘the West’, during the Cold War, some were murdered in cold blood by border soldiers under instructions to kill.

“I found not only that (in the words of an old Rhodope man) ‘everything is remembered’, but also that the wilderness, those magnificent native glades, have retained the heavy energy of various untold events. Most dramatic were the murders of young people from the Eastern bloc, including Bulgarians of course, who were sometimes shot on the spot by border guards. These stories remain undiscussed, but they are key to understanding and coming to terms with our recent past. And therefore our present. Our present is proving very difficult, as a society we seem to be going backwards.”

“I found not only that (in the words of an old Rhodope man) ‘everything is remembered’, but also that the wilderness, those magnificent native glades, have retained the heavy energy of various untold events. Most dramatic were the murders of young people from the Eastern bloc, including Bulgarians of course, who were sometimes shot on the spot by border guards. These stories remain undiscussed, but they are key to understanding and coming to terms with our recent past. And therefore our present. Our present is proving very difficult, as a society we seem to be going backwards.”

This border has always been soft for some and hard for others, the writer maintains, giving today’s refugees as an example. The border which was so deadly to us in the Eastern Bloc is ultra-hard – and occasionally deadly – for them now. However, the corridors and paths of traffic haven’t changed since the Cold War, one of the ironies of the border zone: the corridors remain, only the direction of travel changes.

“The new fences between Bulgaria and Turkey and Greece and Turkey are really ghostly manifestations of the old fence, the Soviet one which was alarmed and electrified to stop us from getting out,” she says. “The cost of these new fences has been ruinous to the governments paying for them, and ruinous for the precious native forests of Strandja, national treasures which are irreplaceable. These fences are an expression of our collective fear and ignorance. And a mirror in which we can see our reflections – and examine our reasons for wanting new ‘installations’ of this kind. Especially when we, as a post-totalitarian society, have insiders’ knowledge of the injustice of borders. This is the irony that we must reflect on, if we wish to know ourselves as a society – and as individuals. What are we really afraid of? Perhaps our own shadows.”

Kassabova heard the same stories in three languages, on each side of this triple border. Stories of traumatic ancestral displacements, evictions, border curfews, and impossible moral dilemmas for the people of the border villages and towns. We need to talk, the author maintains, about this shared past, about what is happening now, in order to protect ourselves against the tragic repetition of history.

“The worst thing we can do as a society is to self-censor, to keep quiet, about these human experiences that make up history with a capital H. Suppression, intimidation, and fearful silence amount to double murder, double annihilation. Whenever an important human story is not told, it repeats itself in time. This is why I believe in storytelling as collective therapy. We must listen to all the voices, not just the official version that comes from above and closes us down. For examples, have we really heard the stories of today’s refugees? The ones that ordinary Bulgarians are so afraid of? It is essential to hear another’s story, to shut up for a while and listen. Otherwise we are condemned to unhappily repeat history.”

The greatest borders we must overcome are our inner borders: prejudice, ignorance and fear of the other. People are the same everywhere and live with the same hopes and pains. The border zone showed me this. No matter what the surface differences are.

“Sooner or later, every border fence falls. And this gives me hope.” Kassabova says in conclusion.

A young Bulgarian artist decided to leave this world in the middle of the past century in order to preserve his incorruptibility, even though he was defeated by the system on a purely physical level. Currently, in the gallery of the..

Musical, culinary, folklore events… the event program in Bulgaria is saturated, so much so that experts are already talking about how the alarmingly growing number of new festivals should be limited. "A clear strategy is needed: which existing..

Bulgarian society knows very little about the Bulgarian emigrants to Argentina. The curious story of the path of our compatriots to the South American country and the threads by which they are connected to their ethnic roots thousands..

A young Bulgarian artist decided to leave this world in the middle of the past century in order to preserve his incorruptibility, even..

Musical, culinary, folklore events… the event program in Bulgaria is saturated, so much so that experts are already talking about how the alarmingly..

+359 2 9336 661