They say people should keep their doors tightly shut during local election campaigns. The streets are teeming with energetic renovations and before you know it, someone could be asphalting your hallway or paving your garden. Banter aside, architecture, municipal infrastructure and urban planning determine the living conditions in municipalities and this is particularly evident in big cities like Sofia. We talk to Prof. PhD Arch. Todor Bulev, who is a university lecturer, researcher and author of numerous urban planning projects.

Common city planning has become increasingly popular in twentieth-century urban planning because when projects are developed individually, it creates an atmosphere of disharmony in the city. A master plan is one that encompasses the city as a whole, explains architect Bulev.

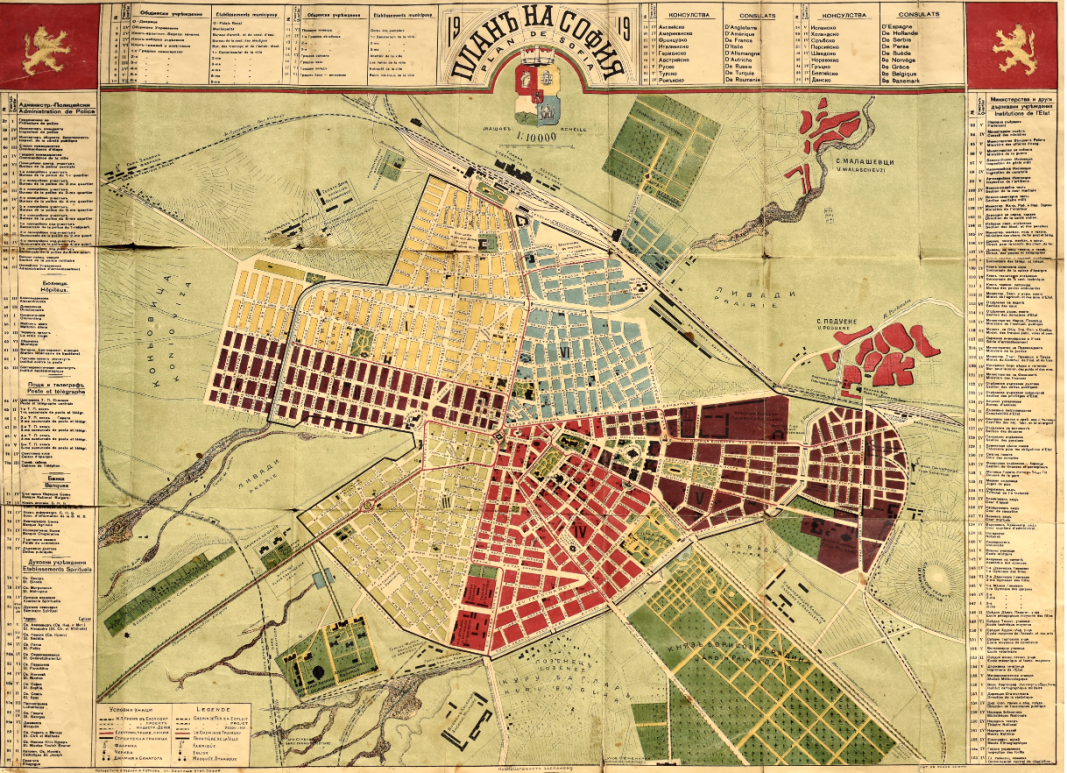

"The first land use plan of Sofia, although it can be conditionally called such, was commissioned immediately after the Liberation (from Ottoman rule in 1878 - ed.). It was within the scope of the current boulevard ring, consisting of the boulevards "Patriarch Evtimiy", "Vasil Levski", "Skobelev", "Opalchenska" and "Slivnitsa". This was the whole city at that time. Today it is the inner part of the historical heart of Sofia. Then the city began to grow, the villages around it joined. Adolf Muesmannn's 1938 city plan* was made just at the time when Sofia had already reached relative stability in terms of growth. Its population was about 300-350,000."

As an extension of politics, urban planning regulates common urban spaces and imposes limits on the ambitions of individuals and institutions. Complete freedom of expression in the city is impossible and urban planning regulates the relations between people so that, as Aristotle said, they can live together with a noble purpose, explains Arch. Bulev.

The German architect reconstructed the Tsarigradsko Shose boulevard, and according to the plan the road was to pass through the parade court of the Tsar's palace in the centre of Sofia. The monarch declared that he would comply with the plan.

"The good thing about the Muesmann Plan is that it is very clear and that is why it is still quoted, but some of its ideas are more or less forgotten today. The most important of these is to shape the city as a group of neighbourhoods, relatively autonomous, separated by wedges of green space, with the centre itself also to be separated by such green space. In a sense, this is a utopian plan, as it hardly gives way to industrial development. But this basic idea is very relevant. It introduces several development zones with very clear height regulation. That is what we are lacking now - height regulation, which has almost been abandoned, and we see buildings of different heights sprouting up quite randomly in Sofia, turning the city into some kind of strange conglomerate."

The Muesmann Plan projected that Sofia's population would grow to a maximum of 500,000 people, with streets designed for about 65,000 cars. But as early as 1965, the population of Sofia had grown to over 800,000. In 1985, the city already had over 1.1 million people. Today, the population is over 1.35 million. There are over 1 million registered passenger cars alone. Together with buses and vans, motor vehicles approach the number of residents. Rapid growth requires new urban planning, but unfortunately it is constantly catching up, not leading the way.

Until 2006 the urban plan of architect Lyuben Neykov, drawn up in 1961, was in force for Sofia. It was essentially a continuation of Muesmann's plan and defined the development of the city to the east and west towards the new districts of Mladost and Lyulin, unkindly referred to by Sofians as "bedroom cities". In 2006, the parliament approved by law a new urban plan that attempts to curb the arbitrariness of developers and landowners.

"The city is still based on the principles that people have equal rights to space, to air, to sunlight, to free access to greenery and so on. At the moment, despite the law and the existing master plan, there are many things happening in Sofia that were not envisaged in the plan at all, but developers have found loopholes to make them happen. One of them is the tendency to build quite tall buildings in places that are often not suitable for them. We are overdue in creating very clear rules and criteria for assessing the exact impact of a tall building on the surrounding area - there is no such thing in Sofia yet."

With a chuckle, the architect recalls how in the 1990s he talked to landowners who found the concept of urban planning absurd and asked, "How come I can't do as I please on my own land?" Enforcement of a law, however good or bad it may be, depends on how well the community accepts it. Make no mistake - the building of cities is largely governed by economic logic. What urban plans try to do is reconcile that logic with social logic and social justice, the architect points out. Listing specific tall towers piercing the sky of Sofia in familiar or unfamiliar places, the conversation moved on to the topics of the city centre, the outskirts of the city and the fate of archaeology in the Serdika-Sredets reserve. You will be able to hear and read about all of them in the continuation of the interview with arch. Todor Bulev for Radio Bulgaria.

*Famous architect prof. Adolf Muesmann from Dresden, Germany, designed the urban plan of Sofia in 1938. His urban planning projects have been realized in Stuttgart, Düsseldorf, etc

Photos: Ivo Ivanov, personal archive

Translated and posted by Elizabeth Radkova

The clock on the facade of the State Puppet Theatre in Stara Zagora has long been a symbol of the city. It was set in motion in 1977 and is unique on the Balkan Peninsula. The theatre recently shared details about the clock on its Facebook page after..

"Every day, we should think about peace and the messages that politicians send,” journalist Tsvetana Paskaleva, who has been living in Armenia for 30 years, says. "The situation around us and in neighbouring countries is unstable and..

Conservationists from Bulgaria Bird Walks are organising a birdwatching walk in Varna today to observe water fowl and forest birds. Two walks are planned in the Sea Garden at 9.00 and 13.00. There will be similar outings every month in the city, said..

"Every day, we should think about peace and the messages that politicians send,” journalist Tsvetana Paskaleva, who has been living in..

The clock on the facade of the State Puppet Theatre in Stara Zagora has long been a symbol of the city. It was set in motion in 1977 and is unique on..

+359 2 9336 661